A Brief History of the Pu`u `O`o Eruption of Kilauea

![]() Follow site author @kenrubin on Twitter

Follow site author @kenrubin on Twitter

see also, the USGS summary (through 2012)

|

January 3, 2018 marked the 35st anniversary of the Pu`u `O`o eruption on the

east rift zone of Kilauea Volcano. This would be it's last anniversay, as the eruption culminated later in the year. It has the distinction of being the

longest-lived historical rift zone eruption at

Kilauea. It is also the most voluminous (>4 km3)

and one of the most compositionally variable (5.7-10.1 wt% MgO) in the

Kilauea historic record.

This decaded-long eruption has had many different phases and types of activity over it's long life and continuous to amaze with its persistence. It has produced a broad field of lava flows

that have buried over 120 sq km of the volcano's south flank

and poured into the Pacific Ocean, adding more than 230 hectares of new land to the island. In 2014 it sent lavas far to the NE, a first for the erupton, extending sme 20 km to the outskirts of the town of Pahoa.

In 2018, it sents lavas into the Leilani Estates and nearby neighborhoods of the Lower east rift zone, causing wide scale devastation. |

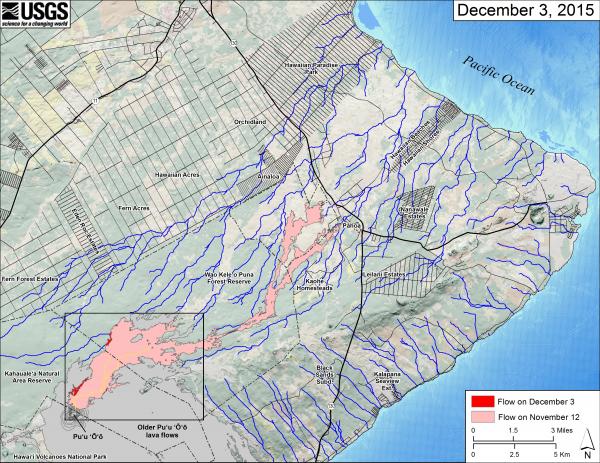

USGS-HVO recent recent flow field map highlighting lavas erupted since Nov 27, 2014 in pink/ref (click for larger image). Older parts of the flow field are in gray (see maps below for full details). Blue lines show steepest-descent use to estimate possible areas of flow advance.

USGS-HVO recent recent flow field map highlighting lavas erupted since Nov 27, 2014 in pink/ref (click for larger image). Older parts of the flow field are in gray (see maps below for full details). Blue lines show steepest-descent use to estimate possible areas of flow advance. | ||||

|

By June 1983, the activity had localized to one central vent and there it stayed for the first 3.5 years (and 44 eruptive episodes) of the eruption. At times, spectacular lava fountains (up to 460 m) high could be seen throughout east Hawaii. During this period, the eruption settled into a regular pattern of brief eruptive episodes, each lasting less than 24 hrs (with the exception of the-384-hr-long episode 35A) and each separated by repose periods averaging 25 days. The fallout of cinder and spatter from the towering lava fountains built a cone at the Pu`u `O`o vent that was measured to be 255 m high by HVO. During this time, a shallow magma reservoir developed beneath the Pu`u `O`o vent. The reservoir was estimated from ground deformation to be 1.6-km long, 2.6-km deep but only about 3-m wide. This reservoir was open at the top, which promoted rapid cooling of the magma (believed to be at a rate of ~5% in 20 to 30 days). In July 1986, the locus of lava production abruptly shifted 3-km downrift to form the Kupaianaha shield, which was active nearly continuous until early 1992 (Kupaianaha means "mysterious one" in Hawaiian)-see image at right. With this vent shift came a new eruption style: continuous, quiet effusion from a lava pond replaced the episodic high fountaining. Overflows from the pond built a broad, low lava shield. In November 1986, lava from Kupaianaha reached the ocean, some 12 km away. It covered the small community of Kapa`ahu in its path. Over the next five years, much of the lava erupted from Kupaianaha streamed directly into the sea via a lava tube system that led from the lava pond to the coast. |

Images courtesy of HVO

Kupaianaha lava pond in December 1986. It is 100 m in diameter. image has been edited by this site author for color balance |

|||

|

In 1990, the eruption entered its most destructive phase when flows flooded the village of Kalapana. Over 100 homes were destroyed in a 9-month period. Eventually, new lava tubes formed, diverting lava away from Kalapana early in 1991; Lava resumed ocean entry within the confines of the National Park. The volume of lava erupted from Kupaianaha declined steadily through 1991, particularly during and after episode 49, a 3 week period during which new vents formed along the rift zone in between Kupainaha and Pu`u `O`o. In early 1992, the Kupainaha vent died, marking the end of episode 48 of the eruption. The eruption shifted back to to Pu`u `O`o in early 1992, where flank vents on the west and southwest sides of the cone constructed a new lava shield. Lava effusion has persisted more or less continuously at this location through the present, except for a brief eruption at Napau Crater, a few km to the west of Pu`u `O`o in late January 1997, followed by a two-month pause in activity at Pu`u `O`o. For the next 17 years, lava flows typically fed from the vents through lava tubes to the ocean, with a few spectactualr episodes of surface flows in between, and a general collapse of the main Pu`u `O`o cone. Only a small remnant remains today. In 2013, activity changed substantially, feeding NE along the rift zone, instead of down to the sea. This was new terriroty for the eruption. First came the two relatively short-lived "Kahauale'a" eruptions, followed by the "Jine 27th" flow in 2014. This lava tracked far down the rift zone, at one point entering a system of old fissures and re-emerging down slope, and eventually reaching within 100m or so Hwy 130 in of Pahoa town. Since mid 2015, activty has continued along the June 27th tube systrem but has been restucted to areas within about 7 km of Puu Oo.

You may be wondering just how much lava issues forth from Kilauea during an "average" Pu`u `O`o eruption day. Unfortunately, lava production rates are difficult to estimate. They appear to have fluctuated but have remained vigorous (300,000 to 600,000 m3/day) with no signs of slowing down or stopping over the long-term. However, the volcano did undergo a 24 day hiatus in all eruptive activity in early 1997, as it has done periodically in the past. There is thought to be a well developled magmatic plumbing system connecting the mantle source for the volcano (where rock is first melted to form magma) with the eruption site. Although the longevity of the current eruption is unique in the brief era of scientific observation at Kilauea, occasional long-lived rift zone eruptions during each 1000 years or so have probably been significant in building up the volcano [For instance, Delaney, 1993 (full reference is given below) estimated that the east rift zone may have experineced eruptions that lasted for most of a century]. With this sort of history, there is no reason to expect that this eruption will end any time soon simply because it has already lasted for so long. On the other hand, little is known about why some long-lived Kilauea east rift zone eruptions, like the 1969 to 1974 Mauna Ulu eruption, abrubtly stop. You may be wondering what happens when molten lava interacts with the sea? Well, as indicated above, new lava has moved down the south flank of Kilauea through well-established lava tubes to the coastal plain during much of this eruption. Much of the lava from the tube system enters directly into the ocean and new land is built up (some of which then slides into the sea). In the process, a spectacular steam plume is created. This steam cloud is composed of predominantly water vapor, but also has a significant amount of SO2 (derived from S in the lava) and Cl (derived from sea water) in it, as well as tiny shards of volcanic glass. This situation makes viewing the eruption up-close hazardous to your health and contributes to the volcanic smog ("vog") that has plagued the southern parts of the Big Island (and other parts of the state) during this and other eruptions. | |||||

|

|

|

|

||

| HCV Home | Hawaiian Volcanoes | Loihi | Kilauea | Mauna Loa | Hualalai |

This page created and maintained by

Ken Rubin©,

krubin@soest.hawaii.edu

The information on this page was compiled by Ken Rubin with assistance from personal accounts of Mike Garcia, HVO reports, and published scientific literature.

Other credits for this web site.

Last page update on 3 Jan 2016